/// Photo Mia Cathryn Randøy Chamberlain: Isabel Huse / Photo Ole Jacob Madsen: Tor Stenersen.

Abstract

The influence of radical protests on public attitudes towards social movement actors and issues remains a critical inquiry. This systematic literature review examines the empirical evidence regarding radical effects. The analysis reveals that positive radical flank effects are frequent, though negative effects also occur, especially when protests involve violent tactics. The findings suggest that the clear distinction of moderate factions from radical ones may mitigate negative associations. Importantly, the presence of radical factions does not inherently pose a problem for social movements. Utilizing the elaboration likelihood model of attitude change, we propose cognitive elaboration as a potential mechanism through which radical flank effects manifest. Future research should aim to replicate studies examining nonviolent radical tactics, such as sabotage, perform meta-analyses to aggregate effects, and explore variations in radical flank effects across different political issues.

Introduction

At the time of writing, activists have blocked several entrances to Norway’s ministries for a week (Matre et al., 2023), protesting a wind turbine plant the Supreme Court has ruled in breach of Sami human rights (HR-2021–1975-S). The act, civil disobedience, stems from the nineteenth century philosopher Henry David Thoreau (2001) who coined the term, and it refers to disobedience against the state, understood as politically motivated, nonviolent lawbreaking.

Civil disobedience is not uncommon throughout Norway’s more than thousand year history, and was in fact an essential part of the Norwegian resistance movement during the Second World War (Madden & Here, 1970). Later, civil disobedience has most commonly been used in environmentalist activist actions, such as against power plants during the Mardøla actions an the Alta actions in the 1970s, against the gas plant in the early 2000s, and more recently against deposition of mining waste in Førdefjorden and Repparfjorden (Gulowsen, 2019; Vinthagen & Johansen, 2022).

Protests actions such as blocking ministries and movements such as Fridays for Future actualise civil disobedience in the present (Richardson & Elgar, 2020). Nevertheless, there is variance in the use of this protest tactic within the environmental movement. For example, Friends of the Earth Norway do not use civil disobedience, but on occasion support other’s use of it (Gulowsen, 2022). Nature and Youth on the other hand, use civil disobedience but only as a last resort in particular cases (Aresvik, 2021). In contrast, more newly established groups such as Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil base their activity primarily on civil disobedience (Extinction Rebellion Norway, 2023; Stopp Oljeleitinga, 2023).

Scholars and activists use examples of militant factions of the civil rights movement and women’s movements to show how radical tactics can be effective (Malm, 2021; McCammon et al., 2015). Experimental evidence points to a so-called positive radical flank effect (RFE; e.g., Simpson et al., 2022). This entails a shift in perspective, where the existence of a radical faction makes other parts of the movement seem moderate and “reasonable” in comparison. Other experiments have detected negative radical flank effect (RFE), where public support decreased as the cause itself and the more moderate factions championing it, were associated with unpopular disruptive protest actions (e.g., Feinberg et al., 2020).

Historically, different actors within protest movements for social change have often disagreed on what tactics are useful, effective or appropriate (Haines, 1984). For example, fear of backlash created tension between more and less radical groups within both the US civil rights movement and women’s movements (McCammon et al., 2015, p. 166; Haines, 1984, p. 42). The overt question has usually been: what tactics benefit a political cause, and which do not? Or worst of all: Might some tactics slow down or prevent progress? More recently, there has been an ongoing debate within the Norwegian environmental movement (and elsewhere) as an increasing number of new actors/groups/organisations employing more radical tactics have been established (O’Brien et al., 2018).

However, there might be a risk that public discussions about protest tactics become largely based on assumptions and selective historical examples. It seems highly relevant for social change movements to gain knowledge based on structured research on how different tactics within the movement affect public opinion. Does the public typically distinguish between different actors in political movements enough for a positive RFE to occur? Or are new, radical factions a threat to the entire activist movement they exist within? Those who might greatly benefit from such knowledge are individual activists contemplating where to focus their efforts for social change, or larger advocacy organisations struggling to make decisions on how much they should embrace or distance themselves from new, radical actors fighting the same cause.

Research Objectives

We will conduct a structured research literature review in order to answer: How do radical protest actions affect people’s attitudes to political issues related to the actions? Additionally, we wish to review the evidence considering theory on radical flank effect and the elaboration likelihood model of attitude change. The theory on radical flank effect was developed based on historical studies of social movements (Haines, 1984). The reason for applying the elaboration likelihood model of attitude change is to suggest one possible psychological phenomena through which radical flanks effects occur. To our understanding, radical flank effects are a macro phenomenon which concerns the psychological process of attitude change in individuals as well as in broader public opinions. Therefore, applying attitude theory might provide more depth to the analysis of social movement research and secure a psychological perspective when reviewing articles with wide spread methodology and theoretical foundations. To our knowledge these two theories have not been combined in relevant research earlier, and will ideally serve as a pilot study in providing more depth to how radical flank effects might occur. A secondary, exploratory point of departure is what kind of radical protest actions produce a negative, positive or no RFE? Our pilot search revealed a lack of differentiation between nonviolent and violent protests (e.g., Feinberg et al., 2020; Simpson et al., 2022). This could possibly have consequences in relation to finding evidence of RFE. Furthermore, we will attempt to identify weaknesses and gaps in the literature to guide further research.

Theoretical Overview

Radical Flank Effect

Haines (1984) coined the term positive radical flank effect when researching the American civil rights movement. He found that moderate factions of the movement, such as those fronted by Martin Luther King Jr., received record high financial contributions following riots involving the movement’s comparatively militant factions. The findings stood in contrast to common belief in the occurrence of “white backlash” to disruptive riots (Haines, 1984, p. 42). According to Haines, the moderates’ financial gains significantly surpassed the radical faction’s financial losses. The study concluded that the riots motivated donations to moderate factions from other, previously uninvolved populations than those ceasing earlier financial support of militant factions. Haines (1984, p. 32) suggested that radical factions create positive RFE as more moderate factions’ demands through comparison are redefined in a positive light and/or if the radical factions create a “crisis” that moderate faction demands can resolve.

On the other hand, negative RFE might occur, where an unpopular, radical faction sheds negative light on an entire social movement (Feinberg et al., 2020). This is historically of great concern to moderate factions and may cause great divides within a movement (Haines, 1984). Therefore, RFE might be a useful framework to understand findings in an intuitive way and help guide how different movement factions relate to one another.

Davis (2022) has applied the theory to study debated controversies created by radical factions within modern environmental activism. However, based on conversations with Davis, and our own pilot search, it seems that though referred to as relevant theoretical background in interesting social psychological research, Haines’ (1984) radical flank theory does not seem to be well tested empirically. This might be viewed as a weakness to the study at hand. However, it is also arguably a good reason to conduct this study.

The Elaboration Likelihood Model

According to the elaboration likelihood model (ELM): “People are motivated to hold correct attitudes but have neither the resources to process carefully every persuasive argument, nor the luxury […] of being able to ignore them all” (Cacioppo et al., 1986, p. 1032). The ELM is a model of attitude change through persuasion and incorporates the fact that all arguments are not carefully processed. The ELM offers valuable insights into understanding the mechanisms of attitude change within the context of social and political movements, which is central to our study of RFE. Although the model is widely recognized for explaining how persuasive communication can shape public opinion, its relevance here lies in elucidating the different pathways through which RFE might influence attitudes toward environmental activism.

Political movements often aim to shift public opinion, which can, in turn, affect political behavior and policy prioritization (Wasow, 2020). Since RFE focuses on the potential impact of radical tactics in these movements, examining it through the lens of ELM is pertinent. The model proposes that individuals process information through central and peripheral routes (Cacioppo et al., 1986). In the context of our study, this dual-process model helps us hypothesize how radical tactics might lead to attitude change.

For instance, radical activism—such as civil disobedience or media-grabbing tactics—may capture public attention more effectively than moderate activism. This heightened attention could lead to increased issue elaboration, especially if multiple media sources cover the events, thus activating the central processing route. Here, the ELM predicts a more stable and enduring attitude change due to thoughtful processing of the issues involved.

Conversely, when elaboration is limited—either by time constraints or lack of motivation—the public may rely more on peripheral cues, such as stereotypes associated with the activists (e.g., being labeled as «radical»). These heuristics can result in attitudes that are less stable but still significant in shaping immediate perceptions of the movement.

Thus, the ELM’s framework allows us to analyze RFE not just as a social phenomenon but through the psychological processes that drive it. By understanding these mechanisms, our study can more accurately delineate the potential positive or negative impacts of radical flanks in social movements, providing strategic insights for advocacy groups aiming to leverage or mitigate these effects.

Method

The objective of this study was to synthesise relevant research to inform individuals and organisations advocating for social change. To achieve this objective, we conducted a systematic literature review employing mixed methods to synthesise findings.

The employment of mixed methods was necessary due to the vast differences in methodologies used and fields of study the sampled studies were conducted within. We have qualitatively analysed the applicableness of the sampled studies to modern campaigns for social change. To get an idea of how prevalent different radical flank effects are,we have conducted a simple quantitative vote counting (as described by Gough et al., 2012, p. 190). Simply put, we counted how many incidents of negative, positive or no radical flank effect occurred in the literature sample. To secure the validity of our results we attempted to collect a representative sample of studies. With this goal in mind and within this project’s time restraints (6 months), it seemed useful to conduct a structured literature review.

The process began with a pilot search based on an academic discussion article concerning the effect of radical environmental actions on popular opinion (Davis, 2022). Three cited research articles were included in the subsequent review. Additionally, we interviewed the author of the article to gather insights on this specific field of psychological research. The interview led to the identification of RFE as a pertinent theoretical framework for the thesis at hand, and the inclusion of one additional article. Moreover, three relevant articles cited in research from the first stage pilot were also included.

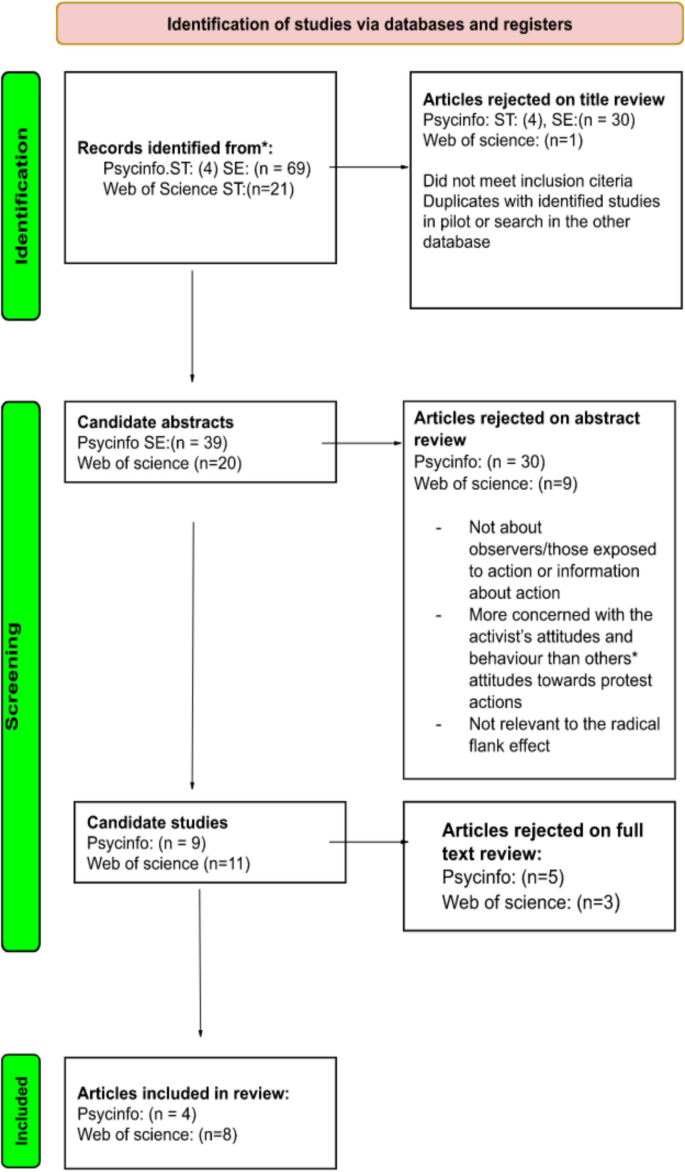

Subsequently, we conducted two structured literature searches in the databases PsycInfo and Web of Science (Fig. 1). One was a theoretically specific search (ST), in both databases, and included the search terms: “radical flank*” and “radical flank effect*”. The broader empirical search (SE) was conducted in PsycInfo using the following search string: (activist* or social movement* or environmental movement* or climate movement* or demonstration* or «political participation» or «collective behavio?r*» or «collective action» or protest* or «social protest» or «social change» or «civil disobedience» or «protest action*» or «non-violent action»).tw. and («climate cause*» or «climate change» or «global warming» or «environment*» or pollution).tw. and (radical* or extreme* or «civil disobedience» or militant*) and (opinion* or attitude* or awareness or public or appraisal* or support* or «public support» or «public opinion» or cognitions* or belief* or view* or impression* or perception* or sentiment* or persuasion* or «emotional response*» or evaluation*).tw.

The synonym function in PsycInfo was utilized to design the search string. The inclusion criteria were as follows: peer reviewed articles, in English or Norwegian, and the research was about attitudes or appraisals of those exposed to what was perceived as radical activism. To narrow the focus, we attempted to focus on environmental protests. Studies that were not centered on environmental protest were included if they fit all other criteria. We have attempted to synthesise findings using Gough et al.’s (2012) description of a thematic summary method, with RFE as the main conceptual frame. We opted for a thematic summary as this method provides valuable insights into highly complex patterns of causation and correlation, characteristics that can describe the topic at hand.

Results

The pilot search identified seven relevant articles to be included in the review. The structured searches identified 12 additional articles. In all, 19 studies were included in the following review. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the structured literature searches and Table 1 shows all identified studies. In the following section we present the main results of the identified studies in separate paragraphs, grouped by design.Table 1 Identified studies

Qualitative Studies

The Audubon Society is known for wildlife protection activism in connection to bird watching. Through in-depth interviews with birders, Cherry (2019) concluded that Audubon Society members engaged in strategic centrism by downplaying their environmental activism to avoid activist stereotypes. Thus, this study provides evidence that some actors consciously placed themselves in the moderate faction of a movement to retain legitimacy.

Dunlop and colleagues (2021, p. 1555) conducted focus-group interviews with teenagers living in areas exposed to fracking, and consequently anti-fracking protests. Participants described the protests as “disruptive, divisive and extreme, disproportionately affecting those already most affected by fracking”. Dutiful forms of dissent were preferred over protests. These involved working for change within the system, such as through “letters”, “petitions” or “speak(ing) to the company” (Dunlop et al., 2021, p. 1548). However, most participants were in fact negative to fracking and several reported being frustrated with the democratic process.

Ellefsen (2018) showed how RFEs change over time in an impressive, 15-year longitudinal study on the animal rights organisation SHAC. Based on historical records and interviews with activists and targeted companies, Ellefsen found that the underground, radical, and sometimes violent faction of SHAC provided an economic threat to businesses cooperating with the animal testing laboratory Huntingdon. Companies commonly claimed that their decision to cease involvement was based on ethics, echoing the moderate faction of SHAC’s arguments. However, according to a Huntingdon executive, companies reported being motivated by fear of sabotage when ceasing contracts with them. Cooperation between radicals and moderates provided this positive RFE for a few years – until the national government retaliated by ordering police repression of all SHAC activity (including moderates). Repression resulted in the end of the campaign due to loss of resources and imprisonment of key actors. RFEs were contingent on different political contexts: In the public arena, destructive factions created media attention which scared companies but subsequent retaliation from the state arena caused negative RFE.

McCammon and colleagues (2015, p. 162) conducted a comprehensive review of “all available historical material” on the Texas women’s movement’s efforts tied to the Equal Legal Rights Amendment. A moderate women’s movement group gained support for meaningful, but moderate, reforms by actively acting more feminine, and politically distancing themselves from the radical group who were seeking amendment change. The moderates committed to a description of themselves as not “one of those women » (McCammon et al., 2015, p. 166). A few years later, the group previously perceived as the radical (“those women”) were able to redefine themselves as moderate in comparison to a new radical faction. Consequently, the former radicals were able to utilise the above-mentioned reform as well as their new, moderate status to succeed in introducing an Equal Legal Rights Amendment in Texas.

Evans (2022, p. 1) proposed a “good cop-bad cop model” on longitudinal change, based on their study of animal rights activism. The model suggested that in contrast to immediate RFE, militant groups can have long term, direct effects such as creating awareness of opposing views which were not already evident in public discourse. Thus, causing institutional change, though more moderate change than they advocated for. For instance, scientists involved with animal testing reported to Evans that they for the first time became aware of animal’s feelings when the issue was raised by radical activists. Several expressed a desire to cooperate with activists to better their laboratory practices, despite activists targeting scientists and their homes. Furthermore, lab reporting practices changed and became more thorough because of activists constantly filing for insight in lab records on animal treatment.

Correlational Studies

Moderate civil rights organisations, received more funding following riots during the 1960’s. For instance, in 1967 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) received 116,7% more in outside funding than the preceding year (no reported p-value). Funds were received from several new donors, in addition to those reallocating their prior support for what became the less popular radical factions. This revealed a positive RFE where moderate groups gained support from new sources.

Through process tracing of industrial parks in Honduras and El Salvador’s apparel industries, Anner (2009) detected a significant correlation between transnational activism and left-union membership (β = 0.122, p < 0.01), and between left-union membership and conservative union membership (β = 0.448, p < 0.05). In other words, a positive RFE occurred where increased unionisation in left-leaning unions was followed by a seemingly reactive increase in conservative union membership. Furthermore, it was revealed in interviews that conservative unions also gained workplace influence because businesses feared leftist union demands.

Farrer and Klein (2022) detected a decrease (−2.69%, p < 0.05) in Green Party vote share in districts that experienced forceful or violent environmental sabotage (e.g., arson or other threatening forms of protest). However, this effect was contingent on the Green Party having some electoral progress in the last years. There was no significant effect in districts where several Green candidates had run unsuccessfully over several years. In other words: there was no backlash where the political situation legitimised extreme environmental concern. A secondary finding was that forceful/violent environmental sabotage did not appear to prime voters on “law-and-order or security issues», a common consequence of protests perceived as terrorism (Farrer & Klein, 2022, p. 223). Thus, the voters seemed to distinguish terrorists from radical activists.

Isaac and colleagues (2006, p. 46) found evidence of inter-movement positive RFE. Time-series observations revealed how the 60’s mass movement for social justice (including leftist feminist and anti-war protesters) provided vocabulary and change-perspectives that “revitalised” unionisation in the US. This research estimated that around a 40% gain in public-sector unionisation could be attributed to inter-movement effects. Protest activity alone correlated significantly with union density increase (β = 1.011, p < 0.001). There was also an increase in collective bargaining rights mediated through workplace militancy over unionisation rights (β = 0.961, p < 0.001). However, no effects were evident in the private sector. According to Isaac and colleagues, this was an example of unions actively utilising a radical mass movement to inspire and implement more mainstream societal changes.

In 2012, Bill McKibben and the organisation 350.org, identified the fossil fuel industry as “public enemy number one” and advocated divestment from fossil fuels (Schifeling & Hoffman, 2019, p. 213). Schifeling and Hoffman conducted a network text analysis of US newspapers to study effects of the divestment campaign. What the researchers deemed more moderate demands, such as carbon tax, moved from peripheral to becoming central media issues following the divestment campaign launch. In fact, eigenvector centrality scores for moderate climate issues grew by 97% on average within the year 2012 (no p-value. Robustness checks: Schifeling & Hoffman, 2019, p. 223). In addition, radical divestment demands gained more media attention when translated into financial language and separated from the radical actors. Schifeling and Hoffman (2019, p. 224) concluded that a positive RFE occurred where “[…] the growing attention to radicals triggers the greater inclusion of eclipsed critical ideas”.

Wasow (2020) conceptualised the Democratic party as a moderate faction within the civil rights movement. Regression analysis based on a broad array of data sources showed that Democratic vote share significantly decreased (2.2–5.4%, p < 0.0001) in districts exposed to violent protests. Conversely, in districts exposed to civil disobedience tactics (nonviolent lawbreaking), Democratic vote share significantly increased (1.6–2.5%, p < 0.0001). The media commonly differentiated between civil disobedience and violence, framing the former as safe and legitimate. Wasow hypothesised that this media sensitivity to different protest tactics might have partly caused the increase in Democratic vote share.

Meta-Analysis and Review Article

Tompkins (2015) conducted a meta-analysis based on data from The Nonviolent and Violence Campaigns and Outcomes project database. Here, the existence of radical factions made both movement gains and losses more probable than upholding the status quo. Radical flank existence correlated most strongly with decreased mobilisation (OR = 1.67, p < 0.01), and higher likelihood of state repression, such as arrests or intimidation (β = 0.82, p < 0.01). The study concluded that negative RFE in the form of decreased mobilisation was most likely but might be contingent on repression (β = −0.21, p < 0.05). Surprisingly, radical flanks also correlated with increased mobilisation (though only marginally significantly, OR = 0.91, p < 0.1) and success in a given year (β = 0.44, p < 0.05). Tompkins (2015, p. 131) concluded that radical flanks are not necessarily harmful to a movement, if “employed correctly”, but did not elaborate on what correct employment entails.

In a theory-generating review of the American religious field, Braunstein (2022) found that the rise of the radical Religious Right created two kinds of backlash. The strongest evidence detected a broad backlash (negative RFE), as the Religious Right’s growth coincided with a decrease in religious identification in the US-population (5% atheist or agnostic in 1972 to more than 23% in 2018). Narrow backlash (positive RFE) benefitted the tactically moderate “Religious Left”. They did not experience a large increase in group identification but did gain political capital, because many political actors wished to combat Trumpism associated with the Religious Right.

Experimental Studies

Bashir and colleagues (2013) conducted a series of experiments and an internal meta-analysis. They concluded that activist stereotypes enhanced resistance to social change. Participants reported significantly less interest in affiliating with a “typical” environmental or feminist activist than an “atypical” activist (r = 0.32, p < 0.05), and unwillingness to engage in pro-change behaviours advocated by the typical activist (r = 0.16, p < 0.05). The typical activists had nonviolent, but more confrontational tactics than the atypical activist. An unweighted means approach did not significantly change the results above (Bashir et al., 2013). However, use of unweighted means revealed a lack of significant difference between wish to affiliate with an atypical activist compared to a neutral person (r = 0.10, p < 0.05), and showed no significant difference on behavioural intentions (r = −0.01, p < 0.05).

Feinberg and colleagues (2020, p. 1) hypothesised the activist’s dilemma, where radical protest actions gain more attention than conventional protest tactics but run high risk of undermining popular support. They conducted six experiments where they exposed participants to both right- or left-wing activism and controlled for political ideology. “Extreme” protest actions (e.g., arson or blocking highways) were significantly viewed as immoral, and participants in the experimental condition identified significantly less with and had less support for the movement (negative RFE). The researchers concluded that lack of identification through perceived immorality were mechanisms through which popular support decreased (serial mediation tested in Study 4: r = −0.27, p < 0.05).

In two experimental studies, Simpson, and colleagues (2022) exposed participants in the treatment condition to information about a radical and a moderate version of animal rights- and anti-fossil fuels activism. One radical faction advocated violence against meat producers, the other damaged fossil fuel producers’ property. Positive RFEs were detected in both experiments. The treatment groups identified significantly more with (both experiments: p < 0.001), had more support for (E1: p < 0.05; E2: p < 0.01) and were more willing to act on behalf of (E2: M = 53.13 vs. M = 48.88, p < 0.01) the moderate factions than control groups only exposed to the moderate faction (see all effect sizes in Simpson et al., 2022, p. 4). Interestingly, RFEs were driven more by different tactics than different political agendas.

Natural Experiments

Muñoz and Anduiza (2019) studied the effects of riots in an otherwise nonviolent movement. Comparison of surveys administered before and after the riots revealed a negative RFE. Following the riots, support for the Spanish 15-M movement (activist movement spurred by the financial crisis) decreased by 12% on average (p < 0.01). The effect was weaker in populations who’s voting history suggested they supported the cause (−6,8%, no reported p-value).

In a preview article, Ozden and Ostarek (2022) described their nationally representative UK opinion poll, measuring public opinion of Just Stop Oil and the more moderate climate organisation Friends of the Earth. The poll was answered before and after Just Stop Oil blocked the M25 motorway for a week as a climate protest. Awareness of Just Stop Oil correlated positively and significantly with identification with (estimate = 0.15, p < 0.001) and support for Friends of the Earth (3,3% increase in support, corresponding to around 2 million individuals, p < 0.001). Support for climate policy also increased significantly (M = 4.28 vs. M = 4.49, p < 0.001), but did not correlate with awareness of Just Stop Oil and therefore was attributed to other climate events at the same time.

Finally, in a preview article, Kenward and Brick (2023) administered a questionnaire before, during and after Extinction Rebellion’s (XR) large-scale blocking of several London motorways. Learning about XR was associated with heightened concern for climate change (d = 0.16, p = 0.010). A lab-experiment was also conducted exposing participants to media portrayals of the protests from either the BBC, The Daily Mail or XR themselves. No significant effect on environmental concern was found but there were other experimental effects, contingent on media sources. There was a small to medium increase in support for disruption in the BBC and XR-conditions (d = ≊0.3, d≊0.6, p < 0.05), and a small effect for dissatisfaction with government action in the XR-condition (d≊0.26, p < 0.05). Overall, those who learned more about the rebellion supported it more, and no backlash was detected.

Discussion

We have limited the discussion to violent versus nonviolent tactics, situations in which positive RFEs occur, mechanisms of attitude change, and limitations.

The Radical Flank Effect

RFEs occur in many different forms and seem to be a relevant phenomenon in the ecology of social movements. Overall, the evidence gathered in this review suggests that radical factions often affect public perception of moderate factions within the same movement, and in some cases across movements, as seen in Isaac et al. (2006) and Anner (2009). Tompkins (2015) explicitly addressed what seemed to be the case in all the studies: when a radical faction appeared, the likelihood of upholding the status quo decreased.

Many studies found more than one kind of RFE (Table 1). Simplified: 12 studies found positive RFE, and seven studies found negative RFE. One study shows a lack of negative RFE, and several showed a lack of effect in addition to detected effects, depending on context or measure. Three studies did not conclude with anything that can be categorised directly as RFE, but arguably shed light on the phenomena.

The Ambiguity of Violence

Despite the inspiration behind this review being nonviolent protests, many of the selected articles were based on radical factions who behaved violently. Either on occasion, such as in the 15-M movement (Muñoz & Anduiza, 2019), or as their main activity, like the radical faction of SHAC (Ellefsen, 2018). In the research objectives we posed the question of what kind of radical protest actions produce which kind of RFE? Based on this review, it seems that negative RFE is more likely if the radical faction is violent (Table 1). In fact, all but one negative RFE was found in studies where the radical faction used a form of violence. Note that Wasow (2020) did not use the term RFE. Nonetheless, we argue that it is valid to categorise their results as RFEs because they suggest a moderate faction of the civil rights movement (the Democratic Party) was affected by the movement’s radical faction (Wasow, 2020). Some studies pointed to a media and public sensitivity to protest tactics, where civil disobedience, despite breaking the law, is presented as more legitimate than violence or aggressive sabotage (Haines, 1984; Wasow, 2020). Furthermore, Farrer and Klein’s (2022) results showed that the public distinguished forceful environmental sabotage from terrorism. In sum, the direction of RFEs appear to be partly contingent on the kind of radical action. However, it might not be as simple as drawing the line between civil disobedience and violence.

There is evidence that violent tactics created positive RFEs. Haines (1984) found positive RFE after violent riots, and Simpson et al. (2022), Evans (2022) and Ellefsen (2018) found positive RFE in connection with tactical sabotage. Though, negative RFE eventually arose due to state repression in the latter study. Interestingly, Feinberg, (lead author of experiments that found negative RFE (Feinberg et al., 2020)), was one of three authors on Simpson et al.’s (2022) paper. Meaning, the same researcher found opposite RFEs in experiments with similar operationalisations of radical tactics. As demonstrated, the findings on RFE and violence are mixed.

How does violence create different kinds of RFE? Perceived legitimacy might be important. In Feinberg et al. (2020) perceived immorality was an important mechanism that caused negative RFE. Conversely, Farrer and Klein (2022) found that forceful or violent environmental sabotage created negative RFE in US elections unless the political situation legitimised a radical response. It would be interesting to see whether negative RFE could have been avoided if The Green Party condemned sabotage, as this was not addressed in the study. In other cases, the repression that violence provoked led to negative RFEs (Ellefsen, 2018; Tompkins, 2015). For example, Tompkins (2015) found the existence of a radical faction to correlate positively with decreased mobilisation post-repression. Also, in Ellefsen’s (2018) study negative RFE first arose post-repression. In the latter, tight cooperation between the violent and moderate factions of SHAC seemed to cause indiscriminate repression from the state. Perhaps violent factions can cause positive RFE if they are viewed as independent from the moderates or if people perceive the context as legitimising violence.

Findings on violent factions are interesting, but it is unclear how well they generalise to for example the European environmental movement, where radical groups so far have been nonviolent (Malm, 2021). On the other hand, perceptions of what constitutes violence likely vary. For example, people may or may not distinguish between physical and economic harm. Several studies did not define terms such as “violence” or “militant behaviour”, and some did not explicitly describe the kind of protest tactics in focus (e.g., Anner, 2009; Dunlop et al., 2021; Tompkins, 2015). For example, Tompkins (2015) studied violence in mainly nonviolent campaigns but also included the Irish Republican Army, who were predominantly violent, just not during the years dealt with in the article. It becomes difficult to generalise findings when neither the violent or normative tactics of campaigns are sufficiently described. Future research should look closer at reactions to different kinds of tactics such as mild sabotage compared to arson.

Positive Radical Flank Effects

Positive RFEs were found in many forms (Table 1) and were not static. Ellefsen (2018) showed how positive RFEs were prevalent until the state sector retaliated, and McCammon and colleagues (2015) showed that what was once a radical faction took a moderate role when a new, radical faction appeared. The latter, together with Anner (2009) and Isaac et al. (2006) also showed how actors actively made use of radical factions to front their campaigns. Thus, activists, NGOs and other political actors can negotiate roles to streamline their influence and policy change.

Several studies found positive effects on public attitudes following disruptive climate activism. Ozden and Ostarek (2022) found a classic, positive RFE where Friends of The Earth gained support when compared to Just Stop Oil. These findings were in line with Simpson et al.’s (2022) experimental evidence which in addition showed that positive RFE could be created by even more radical tactics, such as sabotage. Kenward and Brick (2023) did not directly test for RFE. However, the study detected increased concern for climate change following Extinction Rebellion’s (XR) protest. Hence, there was no negative RFE, and XR’s protest might have provided momentum to the movement by actualising the cause. All three studies found that support for the cause did not decrease following disruptive protests (Kenward & Brick, 2023; Ozden & Ostarek, 2022; Simpson et al., 2022). This suggests, similarly to what Tompkins (2015) concluded, that even in the absence of positive RFE, radical groups such as XR and Just Stop Oil are not detrimental to the climate movement. Replication of these studies can provide valuable information on whether nonviolent disruptive tactics benefit the cause.

Is moderate success positive in the eyes of the radical? To Evans (2022) for example, one could question whether better record keeping in animal testing labs helped animals, or if it made the lab practice more presentable without implementing actual change. On the other hand, Evans (2022) showed how a radical faction did not hurt the cause, despite not achieving as radical change as they wanted. In addition, both Evans and McCammon (2015) show how movements can highball with radical demands and thereby increase the likelihood of deciding bodies landing on a moderate compromise. Moderate change might be viewed as better than nothing. On the other hand, several of the studies showed that RFEs were commonly driven by different tactics, and that moderates could have equally radical political demands (e.g., Ellefsen, 2018; Simpson et al., 2022). In which case, RFE can benefit those perceived as radical as much as the tactically moderate, in terms of policy.

Attitude Theory

Presumably, people are often exposed to activism in short amounts of time, which according to the ELM decreases the likelihood of elaboration (Alcock & Sadava, 2014). In which case, salient features such as people shouting slogans or acting aggressively will be paid more attention to than the message. Lack of elaboration might help explain for example Simpson and colleagues’ (2022) finding that tactics affected attitudes more than message, and Bashir et al.’s (2013) findings on how certain, salient features of activism contributed to negative stereotypes. Perhaps lack of elaboration combined with disruptive tactics leads to unfavourable attitudes about activists.

How can activists attain favourable attitudes? Based on Bashir and colleagues’ (2013) research, activists should use atypical protest tactics to escape stereotypes. Participants wished to affiliate with atypical activists organising fundraisers, rather than typical activists organising rallies. Dunlop et al. (2021) found that youth preferred dutiful forms of dissent to what they perceived as disruptive, anti-fracking protests. However, they were also negative to fracking. This suggests there was potential for an anti-fracking faction with more moderate tactics to gain support in these communities. Strategic centrists, such as birders studied by Cherry (2019), distanced themselves from typical activists. It would be interesting to see whether birders more successfully conserved nature. Arguably, activists could attain favourable attitudes by not being like other activists. Possibly achieved through positive RFE.

Is being likable a good activism strategy? Feinberg et al.’s (2020) activist dilemma illustrates the issue that being likeable often means less media exposure, which is often important for political campaigns. Moreover, it is possible that strategic centrism undermines activism. Prevalent stereotypes might be strengthened when one describes oneself as “not an environmentalist” (Cherry, 2019, p. 762), or not “one of those women” (McCammon et al., 2015, p. 166). On the other hand, McCammon and colleagues showed how a radical faction embodying typical activist traits enabled redefinition of which policies were considered centrist, which resulted in meaningful policy reform. The reviewed studies show that attitudes were often formed by comparing factions within a movement. Perhaps radical activists can be construed as martyrs for the cause as RFE inherently involves one faction being less popular.

Radical factions possibly also create opportunities for elaboration about issues. Kenward and Brick’s (2023) study on XR’s ten-day highway blockade found that one-time experimental exposure had limited effects compared to effects observed longitudinally. Consistent with ELM predictions, it might be that long-lasting protests affect attitudes more because time heightens the chance of elaboration (Alcock & Sadava, 2014). Elaboration makes it more likely that people attend to the message, rather than just heuristics, such as activist characteristics. Perhaps disruptive actions more easily catch media attention and thereby create opportunities for elaboration. Multiple news reports means that people will likely hear about a protest from several sources, and this strengthens attitudes, according to the multiple-source effect predicted by the ELM (Alcock & Sadava, 2014). Additionally, long-term disruptive protests can create pressure on decision makers that moderate factions can utilise. Like when conservative unions gained influence due to leftist unions pressuring factory owners (Anner, 2009). Thus, RFE might partly occur through cognitive elaboration. Future research could consider utilising the ELM to test this mechanism directly.

Limitations

This text discusses several limitations and considerations in research on radical flank effects (RFE) and environmental activism. Firstly, nearly half of the studies reviewed do not focus specifically on environmental activism, which may impact the external validity of the findings. No clear differences in RFE based on political issues were noted, though future research could explore this further. Secondly, there’s a cultural bias in the studies, with most conducted in North America and Western Europe, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to other regions. Thirdly, methodological limitations are evident, with varying methods and measures complicating result aggregation, although the mix of experimental and real-world case studies might offer valuable insights. Many studies are correlational, complicating causal inferences, though effect sizes and significance statistics are generally reported. However, practical significance is often not discussed, a common issue in social psychological research. Further, as described in Gough et al., (2012, p. 190) there are inherent pitfalls to a vote counting approach where studies with different sample sizes are weighed equally. The application of the elaboration likelihood model is experimental as none of the studies utilised this model. However, the application of this framework might offer an interesting perspective on how radical flank effects might occur and provide a useful theoretical framework to further research such effects. The review’s length restriction limits comprehensive result aggregation, and assigning weight to different studies can be challenging due to varying descriptions and methodologies. Despite these limitations, the review attempts to summarize the findings, and a table is provided to facilitate comparison of study features.

Reflexivity

We have utilised a reflexivity document to explicitly address our biases, documenting hopes for certain results or thoughts that differed from study conclusions.

Conclusion

Should moderates fear the radicals in their own ranks? Not necessarily. Through simple vote-counting, implemented as described by Gough et al., (2012) we found positive RFEs to be most prevalent in the studies reviewed. Positive RFE seems to occur more often when campaigns last for longer periods of time, possibly due to the mechanism of cognitive elaboration. This review’s main finding is that it is not necessarily a problem for a movement to have an unpopular radical faction. However, violent tactics seem to increase the likelihood of negative RFE, so there is a limit to how unpopular a radical faction should be. In several cases, violence created negative RFE by provoking indiscriminate repression. Therefore, a movement might benefit from moderates not associating too closely with radical factions. In any case, moral principles conceivably stop many social movements from using violence, irrelevant of whether it is effective. Furthermore, civil disobedience seems to run a much lower risk of negative RFE.

In conclusion, there is empirical evidence that radical protest actions can positively affect people’s attitudes to related political issues by creating a point of comparison which moderate actors and issues within the movement benefit from. There is also evidence that radical actors can reflect badly on the movement but that violent tactics increase this risk. Lastly, we wish to encourage further research on RFEs and other research that can help social movements achieve their goals and provide people with knowledge to make a difference.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

- Alcock, J. E., & Sadava, S. W. (2014). An introduction to social psychology: Global perspectives. SAGE.

- Anner, M. (2009). Two logics of labor organizing in the global apparel industry. International Studies Quarterly, 53(3), 545–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2009.00546.xArticle Google Scholar

- Aresvik, H. T. (2021, April 4th). Natur og Ungdom og sivil ulydighet. Natur og Ungdom. https://gammel.nu.no/sivil-ulydighet/2021/04/mae/

- Bashir, N. Y., Lockwood, P., Chasteen, A. L., Nadolny, D., & Noyes, I. (2013). The ironic impact of activists: Negative stereotypes reduce social change influence. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(7), 614–626. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1983Article Google Scholar

- Braunstein, R. (2022). A theory of political backlash: Assessing the religious right’s effects on the religious field. Sociology of Religion, 83(3), 293–323. https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/srab050Article Google Scholar

- Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., Kao, C. F., & Rodriguez, R. (1986). Central and peripheral routes to persuasion: An individual difference perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(5), 1032–1043. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.5.1032Article Google Scholar

- Cherry, E. (2019). “Not an environmentalist”: Strategic centrism, cultural stereotypes, and disidentification. Sociological Perspectives, 62(5), 755–772. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121419859297Article Google Scholar

- Davis, C. (2022, October 21st). Just Stop Oil: do radical protests turn the public away from a cause? Here’s the evidence. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/just-stop oil-do-radical-protests-turn-the-public-away-from-a-cause-heres-the-evidence-192901

- Dunlop, L., Atkinson, L., McKeown, D., & Turkenburg-van Diepen, M. (2021). Youth representations of environmental protest. British Educational Research Journal, 47(6), 1540–1559. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3737Article Google Scholar

- Ellefsen, R. (2018). Deepening the explanation of radical flank effects: Tracing contingent outcomes of destructive capacity. Qualitative Sociology, 41(1), 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-018-9373-3Article Google Scholar

- Evans, E. M. (2022). Animal advocacy and the “good cop-bad cop” radical flanking of laboratory research. Sociological Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12521Article Google Scholar

- Extinction Rebellion Norway. (2023). Retrieved 11.04.2023. https://extinctionrebellion.no/no

- Farrer, B., & Klein, G. R. (2022). How radical environmental sabotage impacts US elections. Terrorism and Political Violence, 34(2), 218–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2019.1678468Article Google Scholar

- Feinberg, M., Kovacheff, C., & Willer, R. (2020). The activist’s dilemma: Extreme protest actions reduce popular support for social movements. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(5), 1086–1111. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000230Article PubMed Google Scholar

- Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2012). An introduction to systematic reviews. SAGE.

- Gulowsen, T. (2019, January 20th). Ja til mer aktivisme. Harvest Magazine.https://www.harvestmagazine.no/pan/jeg-onsker-extinction-rebellion-lykke-til

- Gulowsen, T. (2022, April 2). Naturvernforbundet støtter sivil ulydighet ved Førdefjorden. Fiskeribladet. https://www.fiskeribladet.no/meninger/naturvernforbundet-stotter-sivil-ulydighet-ved-fordefjorden/2-1-1207281

- Haines, H. H. (1984). Black radicalization and the funding of civil rights: 1957–1970. Social Problems, 32(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.1984.32.1.03a00030Article Google Scholar

- Isaac, L., McDonald, S., & Lukasik, G. (2006). Takin’ it from the streets: How the sixties mass movement revitalized unionization. The American Journal of Sociology, 112(1), 46–96. https://doi.org/10.1086/502692Article Google Scholar

- Kenward, B. & Brick, C. (2023). Large-scale disruptive activism strengthened environmentalattitudes in the United Kingdom. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/vs7p9

- Madden, E. H., & Hare, P. H. (1970). Reflections on civil disobedience. J. Value Inquiry, 4, 81–95.Google Scholar

- Malm, A. (2021) How to blow up a pipeline: Learning to fight in a world of fire. Verso.

- Matre, J., Haugen, V., & Austgard, L. (2023, 2nd March). Fosen-familier møter aksjonistene:− Vi har kjempet i mange år. VG.https://www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/i/8JO061/fosen-familie-moeter-aksjonistene-bra-noen-har-fornuft-her-i-landet

- McCammon, H. J., Bergner, E. M., & Arch, S. C. (2015). “Are you one of those women?” Within-movement conflict, radical flank effects, and social movement political outcomes. Mobilization An International Quarterly, 20(2), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.17813/1086-671X-20-2-1Article Google Scholar

- Muñoz, J., & Anduiza, E. (2019). “If a fight starts, watch the crowd”: The effect of violenceon popular support for social movements. Journal of Peace Research, 56(4), 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343318820575Article Google Scholar

- O’Brien, K., Selboe, E., & Hayward, B. M. (2018). Exploring youth activism on climate change dutiful, disruptive, and dangerous dissent. Ecology and Society, 23(3). https://www.jstor.org/stable/26799169

- Ozden, J., & Ostarek, M. (2022). The radical flank effect of Just Stop Oil. Mendeley Data. https://doi.org/10.17632/rwvskwtfts.1. Retrieved from: https://www.socialchangelab.org/_files/ugd/503ba4_a184ae5bbce24c228d07eda25566dc13.pdf

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Aki, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLOS Medicine, 18(3), e1003583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

- Richardson, B. J., & Elgar, E. (2020). From student strikes to extinction rebellion: New protest movements shaping our future. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800881099Article Google Scholar

- Schifeling, T., & Hoffman, A. J. (2019). Bill McKibben’s influence on U.S. climate change discourse: Shifting field-level debates through radical flank effects. Organization & Environment, 32(3), 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026617744278Article Google Scholar

- Simpson, B., Willer, R., & Feinberg, M. (2022). Radical flanks of social movements can increase support for moderate factions. PNAS Nexus, 1(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgac110Article Google Scholar

- Stopp Oljeleitinga. (2023). Retrieved 11.04.2023. https://www.stoppoljeletinga.no/

- Supreme Court judgement. (2021). Licences for wind power development on Fosen ruled invalid as the construction violates Sami reindeer herders’ right to enjoy their own culture. (HR-2021–1975-S). Supreme Court of Norway.https://www.domstol.no/no/hoyesterett/avgjorelser/2021/hoyesterett-sivil/hr-2021-1975-s/

- Thoreau, H. D. (2001). Civil Disobedience. Mozambook.

- Tompkins, E. (2015). A quantitative reevaluation of radical flank effects within nonviolent campaigns. In P. G. Coy, (Ed.), Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change, (1stedition, volume 38, p. 103–135). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0163-786X20150000038004

- Vinthagen, S. & Johansen, J. (2022). Experiments with civil disobedience during Norwegian environmental struggles, 1970–2000, (Ed.), Civil Disobedience from Nepal to Norway (p. x-x). Routledge India.

- Wasow, O. (2020). Agenda seeding: How 1960s black protests moved elites, public opinion and voting. American Political Science Review, 114(3), 638–659. https://doi.org/10.1017/s000305542000009xArticle Google Scholar

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital). There was no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Psychology, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1094, 0317, Blindern, Oslo, Norway Mia Cathryn Randøy Chamberlain & Ole Jacob Madsen

Contributions

M.C.C. conducted the study and wrote the main manuscript text. O.J.M. assisted in the study and in the writing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ole Jacob Madsen.

//

Artikkel basert på funnene i denne forskningsartikkelen kan leses i VG.