What does a blood-red sky today signify and how does it relate to a distorted human face, cramped together in fear, despair, and anguish? What sort of trouble is this human face caught up in, what is the reason behind his pain? What sort of connection to the world has left him with wrecked in exhaustion and anxiety, with no other possibility than resorting to the most intense and animalistic of all emotive actions – that of the scream[1]?

If one today visits the National Museum of Art in Oslo, where Edvard Munch’s masterpiece is hanging, one cannot help but think that these questions appear to be recomposed – or that novel aspects of them are beginning to reveal themselves, slowly – making the painting a useful trope for saying something new about the human condition in a time of global climate mutations. This is at least the peculiar hypothesis this short text hopes to qualify, but before we get this far let us just get a few facts straight about this emblematic piece of art.

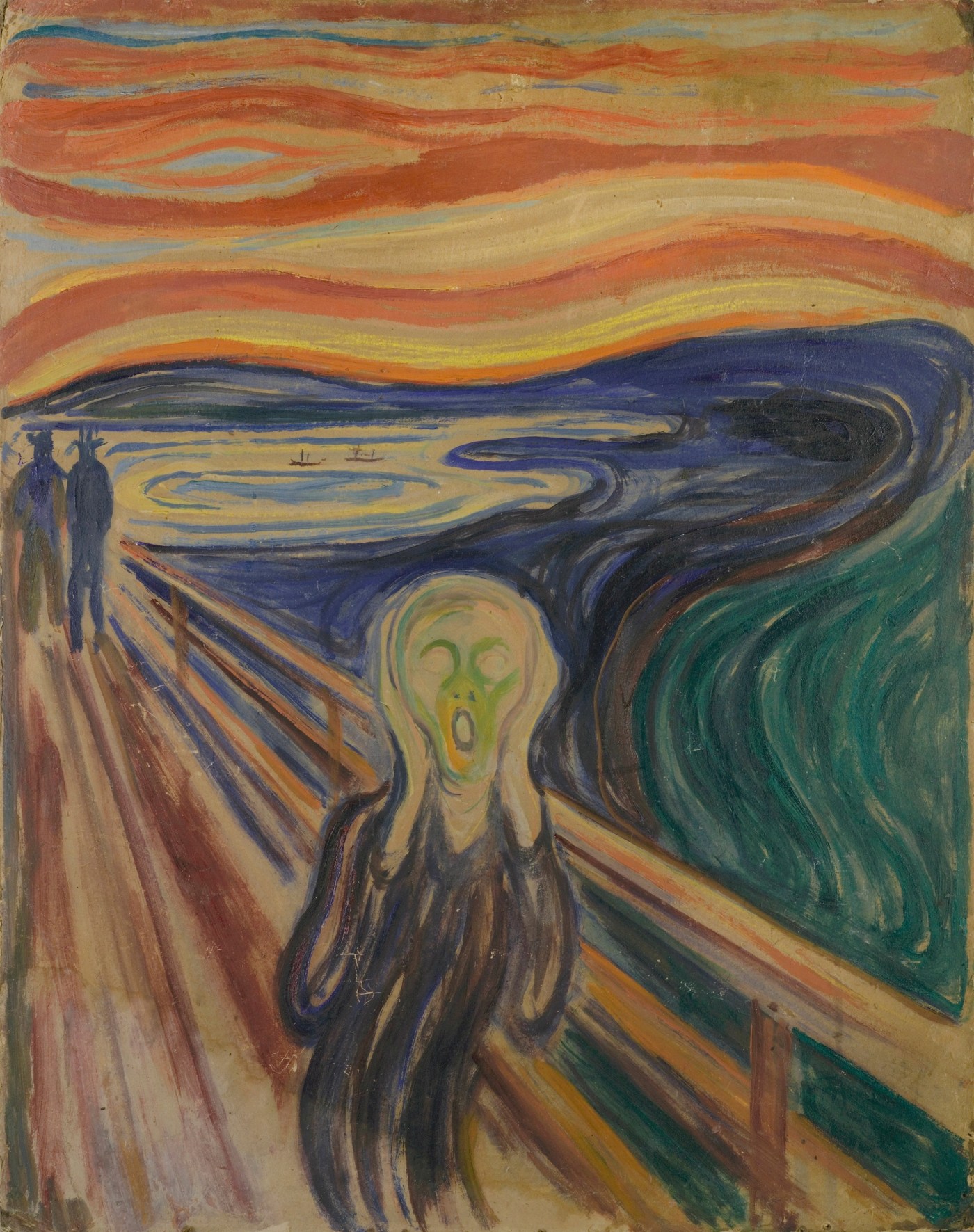

Painted in 1893 and inspired by an actual panic attack suffered by Munch during one of his walks by the Oslo Fjord[2], the famous composition portrays an open-mouthed, hollowed-eyed, ghostly human figure, standing on a bridge, while firmly covering its ears with its hands. Behind him, a landscape as intensely and frighteningly depicted as the human figure itself. Painted with swirling brush strokes hangs a violent blood red sky, somewhat exploding above dark-blue waters, altogether constituting a scenery of chaos, confusion, and instability.

The painting is among the most iconic illustrations of the human figure, and if it has fascinated art scholars, thinkers, and laymen for more than a century, it is without doubt because it captures something universal about the human condition and experience. Here lies the at least the most common explanation behind the Scream’s enormous historical-cultural influence: In 91 cm × 73.5 cm, Munch manages to express the depths of human anguish, anxiety, fear and alienation, offering the viewer a mirror to some of the most painful aspects of what it means to be human in an uncertain, chaotic world.

Because today, not unlike at the time where Munch was painting, we are witnessing a rupture in the human condition and a change in its relation to the world;

In other words, in The Scream we find one history’s most sensitive visual-metaphorical representations of the human being, its relation to the world, and the existential dread, fear, and fright that sometimes emanates from it – and here lies also the intrigue, usefulness, and interest in re-examining this work of art today. Because today, not unlike at the time where Munch was painting, we are witnessing a rupture in the human condition and a change in its relation to the world; a set of transformations that I believe will continue to weigh heavily on its existential attitudes and psycho-emotional landscapes.

‘Landscape’ is not a badly chosen metaphor here, ‘life terrain’ might be even better, because the ruptures we begin to see the emerging silhouettes of are indeed intrinsically related to a set of changes of the land, territories, and soils that we humans live off. Now we are learning that these have another form, intensity and reactivity than we thought it did. What I am speaking of here is, of course, the ruptures brought along by human-induced climate change, and how it not only involves a fracturing of the ground beneath our feet, but also of our life-worlds, minds, and souls. To qualify this proposal, let us turn to a set of historical analogies that might help us understand to what degree this makes useful a reinterpretation of Munch’s painting.

The first analogy is one Bruno Latour held very dear and that he elaborated in his seminal work Facing Gaia (2017). For Latour, the advent of the ‘Antropocene’ epoch marks nothing short of a scientific-cosmological revolution on par with the civilizational adventures of the 16th and 17th century. As he reminds us, in 1633 Galileo Galilei was loathed, laughed at, and inquisited for his claim that Earth was moving around the Sun. Yet, despite being forced to retract his claims by the Church, Galilei still looked up to the sky and down to the ground, stomped his feet and famously whispered the words: “And yet it moves”[3].

Whatever the Inquisition held, the planet was moving – a discovery with enormous scientific, cosmological, political and social consequences. Now, some 350 years later we experience a similar yetdifferent situation. Similar, because scientists once again discover a new set of planetary movements[4]. Different, because what is discovered is not simply an Earth moving. Instead, to use Michel Serres expression[5], it is an Earth being moved. Earth is reacting to the actions of humans. A single verb added, as Latour notes, and we inhabit a new world – one he spent a lot of time on trying to comprehend the cosmological, political, and sociological contours of[6].

What Bruno did not spend so much time on, however, were the inner fragmentations of the human being emerging in the wake of this new outer world, including the terrifying experience, conflicting sentiments, and inevitable existential confusions of being human on a planet driven towards demolition by one’s own species-being’s actions. Let us go back to the many moves, movements and motions at stake today: The planet is being moved by us humans, indeed. But on top of this, we humans are moved by realizing the consequence of our movements! Or perhaps better put: The Earth has been put into motion by us – and newemotions arrive as consequence[7].

I am, apropos, hardly a ‘first mover’ on these topics. Instead, today, every newspaper is floating over with discussions on what analysts term “climate anxiety”, “climate grief”, “solastalgia”, etc. But what these descriptors and diagnostics haven’t yet sufficiently conceptualized is how all these phenomena are but part of a deeper metamorphosis, where Earth and the human’s existential conditions are transforming at the same time – and where the human being is forced to come to terms with having become a Being, an existence, gradually eradicating its own ecological conditions of a livelihood.

An odd, wicked universality of all of us losing the ground beneath our feet[8], followed by an uncanny transformation of the human condition – one that is perhaps best illuminated by comparison with a secondhistorical analogy, especially if we unfold it through both film and theory. Now, last summer everybody was watching Oppenheimer, the brutal story of the director of the Manhattan program, a man who realized that by creating the atom bomb he had become “(…) Death, the destroyer of Worlds”. A bleak Sanskrit statement and a tough realization – one that came with a whole lot of anxieties, hardships and existential scruples for Mr. Oppenheimer, as Cillian Murphy’s sensitive portrayal of him so brilliantly showed.

However, of course, these were not only tough times for the American physicist. Instead, as Karl Jaspers describes it in his extraordinary, existential treaty The Atom Bomb and the Future of Man (1955) this weapon-technological invention meant a fundamental rupture of the human condition. Why? Well, because the human being suddenly had to come to terms with the terrifying awareness that now, humanity could in fact disappear. Before that, there were wars, famines, etc. that could end life here and there, but this was a novelty. Humans had to realize that one of its inventions could end life on Earth, all together – something that had Jasper held as having huge implications for the human’s existential and ethical coordinates.

Tough, indeed. But if we think about it, both the moral and affectual affordances of this awful situation was at least somehow limited – at least compared to the situation we find ourselves in right now. Why? Well, because there was, in a sense, little you could do about it. Of course, you could attend demonstrations or write op-eds for nuclear disarmament., but in the end, the ‘end of the world’ was all in the hands of a few military and political elites who had and have the power to push the ‘red button’, and whose sanity you could only hope restrained them from doing so. But this is different, and a lot more painful: Today, we realize that our livelihood conditions are disappearing due to each of our daily actions, due to each and one of us pushing the button a tiny bit every day.

Now, how’s that for a change in the human condition? In some sense, like poor Mr. Oppenheimer, we have all become “Death, the Destroyer of Worlds” – or at least accomplice destroyers of an Earth System, whose stability our own existence depends on, but that we all contribute to destabilizing each time we buy groceries, visit a clothing store, walk through an airport etc. And I cannot help but to think this is in fact a lot more disruptive of our existential conditions, a lot more disorienting and burdening on our moral and affectual compasses – and in sum, a whole lot more of an agonizing realization to come to terms with.

What are the befuddlements, feelings and fractures emerging, when ‘being human’ means pushing that red button a little bit, all along the way of daily existence?

It was the existential, affectual, and moral implications of this novel condition I took steps towards inquiring in Land Sickness (2023), and that I have since suggested we throw all our resources into shedding light on, under the term of ‘New Existentialism’[9]. What are the befuddlements, feelings and fractures emerging, when ‘being human’ means pushing that red button a little bit, all along the way of daily existence? Those are the issues I believe we need to investigate the configurations of, artistically or theoretically, no matter if we go through historical analogies, film, philosophy… or paintings!

It was quite a detour, my apologies, but the reader now hopefully gets why I am so interested in The Scream today: I think it might allow us to unfold, illustrate and perhaps even sensitize us to certain aspects of this transformed state of the human, and the affectual-moral limbo brought along by it. But before, let us briefly remind ourselves the obvious, namely that no art pieces’ meaning is intransient. Instead, it always transitions and translates differently, in different times. Masterpieces are no exceptions – probably more the opposite – and thus my proposition that Munch’s painting today transfers meaning, in another way.

In what way? Well, when looking at this painting before, many viewers would probably in the blood-red sky find a sort of representation for the anxiety, anguish or dread running through the cramped up human figure; the chaotic landscape sky was a metaphor for the pain of the human being, matching in intensity an inner life splintered to pieces, in a world devoid of certainty, stable anchor-points or meaning. But when gazing at this picture today, one cannot help thinking that the human face is distorted in agony because he has created a burning sky threatening his own existence, because he is the cause of it, because the blood-red sky is the consequence of his own actions!

The figure is agitated because the horizon is literally melting – and because his own being is the root cause behind it. If the reader doubts my re-interpretation, try imagining some 16-year-old kid today, dragged through museum halls by well-meaning parents, before stumbling on this painting, without any prior knowledge of it. Facing The Scream for the first time, what does the kid see? I am pretty sure it would be at least somehow climate-related; In fact, it would not surprise me one bit if our young friend simply thinks that this person on the bridge must be living in Canada, Greece, or wherever wildfires these days caused the sky to turn red, the soot to fall like rain, and humans to fear and flee the unintended side-effects of its own actions.

Now, despite the amusing hypothesis proposed by scientists that certain geological-atmospheric might in fact have affected the red sky in painting[10], we can be pretty sure the human agony Munch felt, fathomed, and sought to portray was not much linked to climatic mutations. But at a moment in history where the sun is on the Holocene epoch, another layer of meaning has been added to this painting, making it a fascinating portrayal of our new human condition – precisely because it captures the interconnected chaos of natural and emotional landscapes, and perfectly depicts the simultaneous, double trembling of the Earth and the human being[11]. Alas – from an infinite scream passing through nature[12] to a finite nature passing through the human scream…. Affects of soil, soul and society, I am afraid, that will only intensify in the decades to come.

[1] Even if it is still a discussion for decades whether the human figure depicted is in fact screaming – or if the screaming at stake here is only to be found in nature. For the argument at stake here, however, it doesn’t matter much. The most important thing here is the human’s agonized face and feelings, and how it can be interpreted to relate to the (natural) world surrounding him, then and now. Yet, see also footnote 13 – but only after reading the text!

[2] Munch created four different versions of The Scream: Two paintings done with tempera paint, and two drawings in pastel and crayon.

[3] In Italian: “Eppur si muove”. However, there is still a lot of controversy about this famous quote. See e.g., Stillman, Drake (2003) Galileo at Work: His Scientific Biography, Mineola, NY: Dover Publications Inc.

[4] Latour considered the discoveries of Gaia-scientists James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis as crucial and emblematic in this context. Whereas Latour held Galileo’s discovery as marking the beginning of modern cosmology, then he saw these Lovelock and Margulis’ discoveries as marking the end of modern cosmology.

[5] See Michel Serres (1990) The Natural Contract, Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press. Ann

[6] On top of Facing Gaia (2017), see Down to Earth (2018) and On the Emergence of an Ecological Class. A Memo (2022), the last-mentioned being co-written with the author of this text.

[7] Or as I put it recently in another text: We are moved by realizing the planet is moving due to our own movements. See Schultz (2025).

[8] On this new universality, see Schultz (2025) and Latour (2018).

[9] See Schultz, Nikolaj (2024) ”On the Many Ways of ‘Becoming Sensible’ in the Anthropocene”

[10] See Olson, D.W., Doescher, R. L. & Olson, M. S. (2004) “When the sky ran red: The story behind the “The Scream””, Sky & Telescope, Vol. 107, Nr. 2, pp. 28-35, on how the eruption of the Krakatoa volcano might have caused the Oslo sky that Munch witnessed to turn red.

[11] This is what I try to capture with the term ‘Land Sickness’, meant to denote this nauseating double-movement of the soil and the human simultaneously. See Schultz (2023).

[12] As Munch himself described the experience influencing his painting. Thus, the old incongruence between art scholars’ interpretation (following Munch’s quote) and popular belief of what or who is screaming in this painting, Nature or the Human, takes on another episode today in a climate-damaged world, because they both are.

//

In recent years, Danish sociologist Nikolaj Schultz (1990-) has emerged as an significant voice in social theory and ecological thought. His work has been praised by scholars such as Dipesh Chakrabarty, Clive Hamilton and Slavoj Zizek, it has inspired artists and curators such as Fontaines D.C., George Rouy and Hans Ulrich Obrist, and in a recent profile, German daily Die Zeit called Schultz a “The Coming Star of Sociology”. Schultz was a close collaborator of late French philosopher Bruno Latour (1947-2022) in the years before his passing. In 2022, Schultz and Latour co-authored On the Emergence of an Ecological Class. A Memo (Polity Books, 2023), a short text on how to construct from below a strong political subject ready to fight for the habitability of the planet in the wake of global climate change. A year after its publication, the book was translated in more than a dozen languages and quickly became a point of inspiration for political actors such as the Green Party in France (EELV) and the German Climate Movement. Later the same year, Schultz published Land Sickness (Polity Books, 2023), currently translated into eight languages, a hybrid text that he calls an “auto-etnografictive essay” on the sociological and existential questions that the Anthropocene force us to pose.

Forsidefoto: Edvard Munch: Skrik. Tempera og olje på ugrundert papp, 1910? Foto: Munchmuseet.

Tidligere artikler i serien / «What is happening to us and our precious world?»:

Arne Johan Vetlesen: Røyken fra krematoriene

Adania Shibli / Reading Philosophy in Palestine

A ‘Finite Nature Passing Through the Human Scream’ / Nikolaj Schultz

Utgitt med støtte fra Fritt Ord.