Johan Rockström is the leading scientist behind the Planetary Boundaries framework, which has had an extraordinary impact on policies and international debates, and which forms an integral part of curriculums for professional climate- and environmental courses in schools and universities around the world. He is Professor in Earth System science at the University of Potsdam, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, co-founder of the Stockholm Resilience Center and chief scientist at Conservation International. Rockström’s research was also the topic of a 2022 Netflix documentary called Breaking Boundaries, based on his book with the same title, coauthored with Owen Gaffney. Among Rockström’s many collaborations, an important milestone is the new assessment of the Club of Rome Earth for All, published in 2022, co-authored with Sandrine Dixon-Declève, Jørgen Randers, Per-Espen Stoknes and others. He serves as one of the chief scientific advisers to the UN, and among the numerous initiatives he is involved in are Planetary Health, Planetary Science Advisary board of COP 30 and Global Commons Alliance.

Anders Dunker: We often think of the environmental crisis as two-pronged, where on one hand, we have climate breakdown and biodiversity loss on the other. There is a risk that these challenges – pressing as they are – end up being perceived as secondary problems politically, with moderate priority, compared to security policy and economic growth. In your work you have drawn attention to the fact that there are as many as nine pressing planetary crises, distinct, but connected, contained in what you call planetary boundaries. You have also one more than most to strengthen the sense of urgency, insisting that we are indeed at a point where everything is decided in three decades.

If I understand you right, this is not only rhetoric. It’s not an exaggeration. It is a description of our actual situation, and it includes the threat of civilizational collapse. How does this picture emerge from the understanding of a wider planetary crisis –where we are now crossing several of the nine planetary boundaries?

Johan Rockström: First we need clarify – what are the nine planetary boundaries? They are the Earth system processes and systems that have been scientifically proven to regulate the state, the resilience, and the life support of the Earth system. These boundaries have now been researched for over 15 years and even though there continues to be some tweaking on the edges, they’ve essentially been verified. For each of these nine boundaries, we have multiple control variables, scientifically robust indicators for the functioning of these boundary processes.

This means that we are able to quantify and define the safe operating space for all these nine boundaries, that is, for world development on a stable planet. And we attempt to determine what happens when we go beyond those safe boundaries.

CC: NASA/Bill Anders

AD: A limit, as articulated in The Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth, is a point where it is impossible to go on. A boundary seems different than a limit – we can cross it, but at our own risk. What happens when we do?

JR: First, we enter what we call the uncertainty range or the danger zone, which is the zone of uncertainty. Scientifically, there is an uncertainty range for all of these because of the interactions between them, which you mentioned earlier. Go beyond that uncertainty range, and you enter the high-risk zone, where science is quite clear that we are likely to cause large scale deterioration of fundamental functions in the Earth system. This means that breaching a planetary boundary does not necessarily mean crossing a tipping point, but the risk increases, particularly when multiple boundaries are breached simultaneously. Crossing tipping points, such as the collapse of the AMOC, or tropical coral reef systems or the Amazon basin, are in generally irreversible for any time-scales relevant for human societies. Once they are triggered, the functioning of the Earth system is undermined (generally shifting from dampening feedbacks that can buffer change, to amplifying feedbacks that accelerate negative change), and contribute to accelerate warming. The latest assessment shows that seven of the nine planetary boundaries are already outside of this safe operating space.

Breaching a planetary boundary does not necessarily mean crossing a tipping point, but the risk increases, particularly when multiple boundaries are breached simultaneously.

AD: So, in one sense, what we need to save or regenerate is above all this safe operating space –

JR: What makes us in the planetary boundary science nervous, is that in the depths of a climate crisis, we’re also breaching the biosphere boundaries – that is, we are outside of the safe space on biodiversity, freshwater use as well as land system change. Especially concerning is the situation for big forest biomes, tropical forests, temperate forests and boreal forests, simply because they store so much carbon and are such an important regulator of freshwater flows.

We’re clearly consuming too much fresh water, both green water in the soils and blue water in the rivers. At the same time, we are overloading the Earth system with nutrients. Nitrogen and phosphorus overloading lead to dead zones and an undermining of marine ecosystems. And we have registered a transgression of another boundary, that of «novel entities» – meaning chemical pollution. At the same time, the 2025 assessment released at the New York Climate Week, shows that the ocean chemical change boundary is also now transgressed – which we define as ocean acidification.

We re undermining the strength or the resilience in the living biosphere, both on land and in the ocean, which we depend on both for our life support in a stable state, but particularly as a cooling factor with respect to the climate crisis. This is what makes us conclude with a very high degree of scientific confidence that we have a planetary crisis on our watch – in our lifetimes here on planet Earth. That’s the assessment that we’re making.

What makes us in the planetary boundary science nervous, is that in the depths of a climate crisis, we’re also breaching the biosphere boundaries – that is, we are outside of the safe space on biodiversity, freshwater use as well as land system change.

AD: At the same time our global consumption keeps rising …

JR: …and with it our use of energy and injection of heat into the Earth system, which is a problem on a very fundamental level. Together with Professor Karina von Schuckmann, one of the world’s leading energy imbalance scholars, I have recently organized a workshop on the planetary scale energy imbalance we are causing through our burning of fossil-fuels and breaching of Planetary Boundaries, with the participation of top scientists in climate physics.

Human activity keeps adding heat to the Earth’s system and heat has to go somewhere. While only 1% of the excess heat is in the atmosphere, causing the temperature rise, 90% of the heat is absorbed by the ocean. 4% is consumed by melting ice in the Arctic and Antarctic, and the mountain glaciers. Another 4 or 5% is absorbed into the soils. The whole system is buffering under stress, and the crucial question is: how long can the system cope with this?

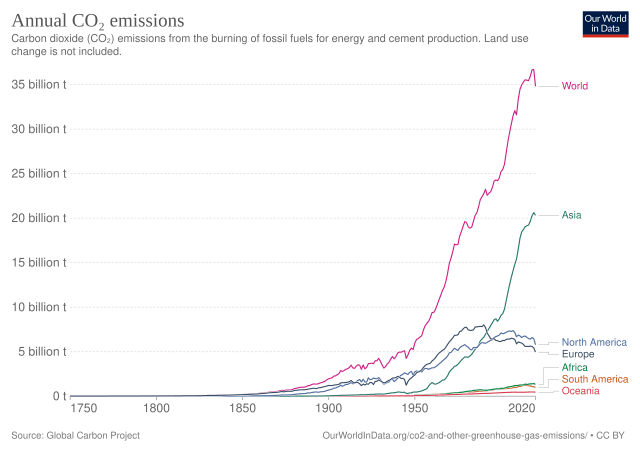

Since the 1950s, when we went into the great acceleration, there has been a dramatic hockey stick graph of rising carbon dioxide and temperatures. But over the past 10 years, the rate of warming has increased – the temperature rise is accelerating. And we’re not even able to explain it fully.

CC: Hannah Ritchie. CO₂ emissions dataset: Our sources and methods How do we construct our global data on CO₂ emissions?

AD: There must be some theories?

JR: One parameter is clouds: When the temperature on Earth increases, you breach the planetary boundary for climate, but it also impacts the freshwater boundary, because you get more vapor in the atmosphere, and you get more intense rainfall storms, but you also get more clouds. And the cloud dynamics are shifting in a way that the planet is having a net warming impact.

Moreover, with a warming planet, more ice melts, ice gets darker, land gets darker, tree lines go further north and further south. The entire planet gets darker and absorbs more heat, resulting in feedbacks shifting from cooling to self-amplifying warming.

What makes us really nervous is what we would see if due to feedbacks, the planet starts shifting its capacity to buffer the disturbance caused by this energy influx. And the nightmare, of course, is if too many feedbacks like these pile up to become self-reinforcing. This could kick the planet of its stability domain, where we’ve resided since we left the last ice age 12,000 years ago, the Holocene equilibrium.

What makes us really nervous is what we would see if due to feedbacks, the planet starts shifting its capacity to buffer the disturbance caused by this energy influx. And the nightmare, of course, is if too many feedbacks like these pile up to become self-reinforcing.

AD: Where are we and the planet headed now?

JR: If our healthy planet dominated by cooling feedback is pushed out of its equilibrium, we start drifting away into a future where the planet is not helping us anymore. That would mean that even if we stop all emissions today, instead of stabilizing, it could drift off in what we call a Hothouse Earth trajectory. We might not be there yet, but in all honesty, we don’t know where we’re heading.

What we are witnessing is like cracks in the resilience of the planet. Temperatures are rising faster than expected. Sea surface temperatures are rising faster than expected. Forest systems are losing carbon uptake capacity. The ocean is acidifying so rapidly that we cannot rely entirely on its stability. These are early signs that make us very concerned.

AD: In your book Breaking Boundaries, one chapter opens with a quote by your colleague Hans Joachim Schnellnhuber. He says «What is the difference between a 2°C world and a 4°C world? Human civilization.» In other words, the notion of a rather narrow time-window, just a few decades, to avoid a global collapse – is quite realistic?

JR: There is one qualifier, though, to your statement, which is the following: When science says that what happens over the next 30, 40 years will determine the future for humanity on Earth, that’s a correct statement – but it’s not a statement suggesting an imminent collapse. It is rather the risk that we trigger irreversible changes that lead to unstoppable continued global warming, a drift towards a state that threatens human civilisation as we know it.

A more than 3 degrees Celsius warmer planet will, very likely, push us across tipping points that could add additional warming. That’s what makes the next few decades so decisive. It’s not that we fall over an escarpment, it’s that we risk pushing on-buttons so that we select a dangerous course and drift off in the wrong direction.

I would argue, and then I think most scientists today would agree – that the window is still open to have a safe landing for a manageable future. I say manageable because we cannot return to a virgin state, but a manageable future.

I would argue, and then I think most scientists today would agree – that the window is still open to have a safe landing for a manageable future. I say manageable because we cannot return to a virgin state, but a manageable future.

AD: What is at stake, then, is the habitability of our planet. But how do you factor in a sliding scale of habitability in your models – where life just gets much harder, more dangerous, more impoverished or painful, long before humans and other species actually perish?

JR: That’s a really good question. And it doesn’t have a direct, simple and straight answer, partly because it depends – of course – on how you define habitability. One way to answer your question is to rely on our social science understanding of what constitutes a minimum level of dignified life (e.g., in terms of access to resources that form the basis for human wellbeing) and significant harm levels, beyond which are morally unacceptable.

In The Earth Commission, that I’ve been co-chairing, we added for the first time social quantifications of the just boundary levels for several of the planetary boundaries. And we measured that in terms of significant harm levels to people. What we endeavored to assess was what – from a justice and moral perspective – is the maximum acceptable level of harm to people, beyond which we end up in unacceptable levels of harm. At what point do you reach what would socially be defined as triggering uninhabitable conditions for humans?

CC: Zero, Public Domain Dedication

And the science from the Earth Commission shows that already when we exceed 1°C, we start seeing evidence of exceeding acceptable significant harm levels, affecting large communities and millions of people. The scientific assessment furthermore shows that if we reach two degrees Celsius of warming, we would expose 2 billion citizens on Earth to life-threatening heat levels. We deem such levels to be completely morally unacceptable, socially uninhabitable. It wouldn’t impact all people on planet Earth, but a significant portion would actually go beyond the threshold of what you scientifically can call – according to much of the literature on the topic – global catastrophic risk. We simply cannot allow ourselves to go there.

AD: Whereas current projections point to at least 2.6 or 3 degrees warming, given the actual trends of climate gas emissions.

JR: If you go to 3 degrees Celsius, you fully enter the terrain of the unknown. Because the last time we had 3 degrees Celsius of warming on planet Earth was outside of the Quaternary, which is the latest and current geological period, which began 2,6 million years ago. A geologist would probably debate me on this, but I would say as soon as you’re outside of the Quaternary, you are on irrelevant grounds of comparison. In terms of continental configuration, in terms of the hydrological cycle, in terms of oxygen, in terms of the ocean conveyor belt of heat and nutrients, in terms of everything that we depend on and that we are familiar with on planet Earth – all this has only existed during the Quaternary. If you push the planet outside of these parameters, whatever anyone tells you, they cannot know anything for certain. I cannot say that we cannot live in such a world, but nobody can promise us that we can live there. What we can say is that there is no evidence that we can support our world, with soon 9-10 billion co-citizens, on a planet outside of the Quaternary. So the question is: Why go there?

If you push the planet outside of these parameters, whatever anyone tells you, they cannot know anything for certain. I cannot say that we cannot live in such a world, but nobody can promise us that we can live there.

AD: In their book Planetary Social Thought, Nigel Clark and Bronislaw Szerszynski have pointed out that, throughout its long history, our Earth has been several different planets. The Earth we know is not just a certain place, it is a certain planetary age that our ways of life are calibrated to. And as you imply, certain earlier Earths would be uninhabitable to us, entirely too cold or too hot. Without the earth as we know it, we would be thrown out of our cosmic oasis, so to speak – we would fall out of our temporal niche.

JR: Precisely. Because it’s outside of the corridor of life over the past 3 million years. And we, as modern humans, have only existed over the past 250,000 years, living through two ice ages and two interglacials, but then we were only a few million people. After the last ice age, we’ve come to this extraordinarily stable Holocene interglacial, when civilizations as we know it took off. Why? Because we could become sedentary farmers, because we could produce food, because the planet suddenly settled down and stabilized, so that you now had rainy seasons and growing seasons that came predictably every year. It is very likely as straight forward as that. We may have had the skills to domesticate animals and plants already in the depth of the Ice Age, but it did not make sense to invest in this sedentary practice, as conditions were too volatile. In the Holocene the environment «calmed down» and temperatures and water allowed us to embark on the civilisational journey that has taken us to the world of today.

As soon as you talk of 3 degrees or beyond three degrees or even 4 degrees Celsius, that is what I would call a collapse point – an existential, catastrophic outcome for humans. Even if there might be some pockets of humans left, nobody knows if we’re talking about a few billion or million people – who knows? The question of how many is irrelevant because it’s basically a catastrophic, unacceptable outcome, where there is no evidence that it will be possible to support the world as we know it.

As soon as you talk of 3 degrees or beyond three degrees or even 4 degrees Celsius, that is what I would call a collapse point – an existential, catastrophic outcome for humans.

AD: It is astounding that all these extreme outcomes and threats have been brought about through the growth that happened since the Second World War – during only one human lifetime. Sir David Attenborough, who introduces you in the documentary film about your work, Breaking Boundaries, says that he literally grew up in another geological epoch: He grew up in the Holocene, and that goes for most of us with our mindset. One might be forgiven for taking Earth for granted and the stability for granted for not being able to adjust to these extreme insecurities?

JR: I agree with you that, in a way, humanity up to quite recently can partly be forgiven for not acting in crisis mode. The planet has been lulling us into this comfort zone, since our Earth has this phenomenal bio-geo-physical capacity to buffer and dampen the unsustainable stress that we’re causing to the system. Our planet acts as a forgiving mother, protecting her miss-behaving children. She appears to be in good shape, when in reality, she’s gradually losing strength in very significant ways. This deception is one factor.

The second most dramatic factor is that for the first time in human existence on planet Earth, we must preemptively veer away from a catastrophe before it occurs. We humans are very talented in rising after catastrophes. This time, we cannot do that because once we crash, there’s no repair. Regret is not an option anymore. And this is extremely challenging for us. We’ve never done something like that before – and now we must.

We also know that the danger is not like COVID or like a drone over Kyiv that hits immediately. If the Greenland ice sheet crosses a tipping point tomorrow morning, it will take at least thousand years before we have a seven-meter sea level rise, but the process would be unstoppable. We would be handing over to our children a planet that just drifts away in the wrong direction. All this is, of course, very challenging.

CC: Gannu03

AD: Given your influence and the nature of your work as a UN organizer, scientists, and public thought leader, you have very direct access to policymakers. You go into dialogues with people from finance, the media, politics – all of these sectors. So, I feel that you are one of the people on the planet that one can actually ask – what is your qualified impression: Do people in power really understand the situation, the gravity of it?

JR: That is a really good question. We’ve been duping ourselves by subsidizing our well-being, particularly in the rich parts of the world. All the while, the planet has been duping us – because it has absorbed extra heat and CO2. Now we’ve come to the end of the road of this because the planet cannot cope anymore, but we’re still stuck in that same logic.

When it comes to your point about being forgiven for not fully understanding, I still don’t want to let anyone off the hook. After the 4th assessment of the IPCC, when the IPCC in 2006 got the Nobel Peace Prize – from that point on – there’s absolutely no excuse for anyone. Nobody can claim ignorance because not only is the science overwhelmingly clear, but it’s also been communicated in extremely understandable ways. Which brings us back to your question: Are the decision makers in our world understanding the gravity of our situation?

With respect to global warming, for the private sector and for business leaders at large, the answer is yes, it is understood. For citizens, the answer is yes, it is understood. And we have proof of that. Professor Anthony Leiserowitz of Yale University, who leads the opinion polls, has repeatedly showed that even in the US, even during the Trump administration, up to 60% of US citizens are deeply concerned about climate change, and they want climate action.

I still don’t want to let anyone off the hook. After the 4th assessment of the IPCC, when the IPCC in 2006 got the Nobel Peace Prize – from that point on – there’s absolutely no excuse for anyone

AD: …even if far fewer people are ready to make it a political priority, also according to polls.

JR: Still, under the surface of all the noise we are subject to, there is a very strong maturity and a strong foundation of sustainability we stand on, of recognizing that we have a problem, and we need to solve it, and that solving it should be a priority. The problem is that we all have many priorities in life – particularly decision makers and political leaders – even though the majority of them, too, understand this.

We should remember that the Paris Agreement was signed by essentially all countries in the world. The Sustainable Development Goals are signed by all countries in the world. The Dubai statement of the climate negotiations, the Glasgow statement of the climate negotiations: We have agreed that 1.5 degrees Celsius is not a goal or a target, but a limit that we have to take seriously and that we need to start phasing out fossil fuels.

But you have a middle group of political leaders – take India, South Africa or Poland – that are not questioning human-caused climate change, but they’re concerned about the costs and about the difficulties of transition. You have countries with massive oil resources, like Norway and Ecuador, which are very engaged in the sustainability journey, but their economies depend on continuing to extract fossil fuels. The world is very messy, and the actors come in many categories. And there’s certainly some denialism out there, but denialists are in an exceedingly small minority.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, signs the COP21 Climate Change Agreement (Paris Agreement) on behalf of the United States. CC: US State Department photo/ Public Domain.

AD: It seems fair to say that soft denialism might be a bigger problem than hard denialism. Hard denialism is a difficult, unreasonable position to hold, but soft denialism peddles reasons for complacency, to make the problem seem less urgent.

JR: I fully agree with you. Nonetheless, it is important to note that full denialism is a very minor phenomenon. I’ll give you just one example to hammer home that point:

President Donald Trump – who portrays himself in public as a diehard denialist – instructs the Department of Energy to kill the national climate assessment in the United States by handpicking a group of climate skeptics to create a report that is unscientific to support his view on climate change. And this report comes out – and virtually every sentence in that report has been proven wrong by a vast majority of scientists. Still – still! – read the report: They’re actually saying: «Dear president, you’re wrong. Humans are causing climate change. It’s just that we think that this is not such a big economic problem. We can cope with this.» And to be honest, from a certain perspective, they are right, because the conventional mainstream climate economics based on general equilibrium modelling and optimization, that are based on damage functions that totally underestimate the true impacts of human-induced climate change. It shows that by 2050, the economies in the northern hemisphere will actually benefit from a bit of warming – and that is also what most macroeconomic models still show.

AD: What speaks against such ideas of calculated risk with respect to climate and environment, is more than anything, the presence of incalculable risks. So far, your answers have focused on climate, but what about the other boundaries? A worst case scenario, would be that all the other boundaries and their tipping points affect each other so that they could cascade somehow, tip each other over like dominoes?

The planetary boundaries determine the resilience of the system, that is, the strength of the system and its ability to handle all forms of stresses, whether they come from microplastics or air pollutants or climate heating. What is at risk right now is the buffering capacity of the earth system as a whole. These are interactive systems, and yes, we also have rising evidence that when we breach one of these boundaries, other tipping point systems become more brittle.

So let us take the Amazon basin as an example. If you look at it only from a climate perspective, it may tolerate up to 3 degrees Celsius of warming before tipping. But we also know that if we lose the canopy cover within the land system boundary and lose biodiversity within the biodiversity boundary and also continue undermining the hydrological cycle within the water boundary, then the system is likely to tip already at 1.5-2 degrees Celsius. So yes, you have interactions between boundaries, and then you have what you aptly described as domino effects.

As a second example, we also have increasing scientific evidence that particularly the ocean system connects tipping point systems. So the most researched one so far is the connections between the melting of the Greenland ice sheet and the slowdown of the AMOC – the system of currents in the Atlantic ocean – and how that in turn impacts the monsoon systems, which can accelerate the dieback of parts of the Amazon rainforest and accelerate the warming down in the Southern Ocean, and thereby also the melting of the West Antarctic ice sheet. So that’s a domino effect between the Arctic and Antarctica via the ocean system. This is not yet in the IPCC reports, and you could still call it cutting edge science.

CC: Dalia McGill

AD: Does that mean we have underestimated the crisis precisely by subdividing it in different sectors – while it is in fact an interconnected mess – what some call a polycrisis?

JR: The definition of a polycrisis is still, largely an academic debate. I’ve been co-authoring on this with Thomas Homer-Dixon – but even the two of us don’t fully agree on the definition! I think we should have an extremely careful and conservative definition of a polycrisis and avoid all inflation in the use of that term.

Let’s say we can have an earth system crisis, and then we can have a geopolitical crisis, we can have a pandemic crisis, we can have a financial crisis, and we can have a crisis of migration. Nonetheless, in my vocabulary, you can only have one polycrisis. And you can only have a polycrisis once, because once you’ve entered a polycrisis, if you don’t solve it, you really, really have irreversible changes to the extent that you’ll never have a crisis of that sort again. You would have a planetary crisis interacting with a pandemic, interacting with a war, interacting with a financial crisis, and all of them add up to reinforcing each other towards a pinnacle of crises.

AD: A sort of scientifically certified pandemonium of planetary problems…

JR: Exactly. And you should save the word polycrisis until we do reach that point. The question then is, do we have a polycrisis today? My answer is no; we don’t. We’re definitely seeing signs of moving towards what could evolve into a polycrisis. But I would say we’re not there yet. In the literature, it’s not really defined as a unique, one-off occurrence. But I think one should rather reserve polycrisis as the strongest word in the vocabulary.

Do we have a polycrisis today? My answer is no; we don’t. We’re definitely seeing signs of moving towards what could evolve into a polycrisis. But I would say we’re not there yet.

AD: Despite the risk of converging crisis, we are very far from making anything like a maximum effort – on national or international levels.

You have presented the idea of an Earthshot, an equivalent of President Kennedy’s Moonshot, that is, the Apollo program which put a man on the moon over 50 years ago. Even back then, protesters shouted «Fix Earth before we leave it». Now it is «fixing the earth» that appears to require an orchestrated effort, which seems so grand and improbable success would seem almost miraculous. What can give us hope to meet the steep deadline set by the earth systems, by the tipping-points that seem to be looming in the very near future?

JR: On October 13th, 2025, we released the second global tipping point report. It provides an update on the negative tipping points we’ve been discussing so far, but it also presents the evidence of positive tipping points. In other words, we are talking about non-linear positive transformations in different sectors and different communities and scales across the world.

There’s a long-standing literature on S-curves and exponential shifts, and the excitement about that evidence, which I think is relevant, dates back to Everett Rogers in 1962 when he presented the theory of diffusion of innovations.

In other words, we are talking about non-linear positive transformations in different sectors and different communities and scales across the world.

AD: Just to clarify, this is an «S»-curve because every innovation creates growth – and when the growth flattens, there is a new innovation window, followed by new growth and improvement? You would need a lot of such dynamics to counteract the dangers you have identified. Is it even thinkable or believable?

JR: The crucial point is that Everett Rogers proved through empirical evidence that for technologies, you don’t have to penetrate a market with more than 20 to 25% of the market share before you can have a takeoff through S-curves of exponential positive tipping points.

If what you are offering the market simply is a better solution than the incumbent, you don’t have to convince more than a fifth of the citizens or the stakeholders. We see that happening for electric vehicles in some countries.But we also see it happening around the world for green energy production, both in wind and solar. And you see it both in developing countries and developed countries. Renewable energy systems are now penetrating in African countries, and it’s happening exponentially.

Positive tipping points can already be found in a few other areas of technology, but you don’t find it yet in the food system. You don’t find it in the built environment. You don’t find it in the steel industry, or in aviation or in textiles or in electronics. So – you know – we still have a long way to go.

CC: kallerna

AD: This is not something you stumble into, then, or something that just happens. Such developments rely on strong intent and a vision. I have seen you quote the French author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: He said that if you want to build a ship, you don’t need to command people around. You just need to paint a picture of the beautiful ocean in peoples mind, and then they will want to set sail – so the ship will be built. This wonderous, yet quite believable and simple effect, seems to be at play in positive tipping points?

JR: Yes, definitely. Thanks to the fact that we do have the empirical evidence that if you adopt sustainable practices and solutions, you become a winner at the other end. And you become a winner in multiple ways. Better economies, better jobs, better health, better security, better resilience, increased levels of stability and peace in society. We didn’t know this five, six years ago, but today we do.

Roger Everett’s theory of diffusion of innovation is that if you have a better solution, then you don’t have to convince everyone. You just have to convince a large enough minority. And then you tip over the passive majority. A significant portion of that majority are not at all denialists. Or they are rather soft denialists. They would rather keep sitting there on the fence, being kind of skeptical, because they don’t like change. But as soon as they’re subjected to a FOMO-moment – when this real and well-justified Fear Of Missing Out sets in – you bet they will run!

//

Portrait photo of Johan Rockström, CC: Karkow / PIK

Norwegian Writer’s Climate Campaign would like to thank Anders Dunker and Johan Rockström for this thought-provoking conversation, and their contribution to our new series «Irreplaceable nature, inalienable relations».

Forfatternes klimaaksjon takker Anders Dunker og Johan Rockström for samtalen og bidraget til vår serie «Umistelig natur. Umistelige relasjoner».

Du kan lese en forkortet utgave av dette intervjuet på norsk hos HARVEST.

//

Å anerkjenne noe – eller noen – som uerstattelig eller umistelig, kan være en transformerende opplevelse. Det er ofte her naturrelasjonen oppstår. Slike erkjennelser melder seg når kjærlighet, beundring og en dyp relasjon til en naturtype settes i kontrast til tap eller trusselen om det. Klodens umistelige natur, og den nærmest hellige kvaliteten på det vi respekterer, beundrer og opplever som verdig, forvandler oss til vitner og kan kalle oss til å virke som talspersoner, beskyttere, aktivister og forkjempere. Menneskeforakten i krigene som føres mot bl.a. ukrainerne og palestinerne er også en forakt for livet til fugler, pattedyr, insekter, jordbruk og planteliv. Kanskje kan større kjærlighet til og respekt for våre slektninger i naturen også bidra til en dypere begrunnet motstand mot krigens logikk, dvs. at hensikten helliger målet om total ødeleggelse, for å oppnå erobringer som eo ipso er en fornektelse av historisk kunnskap, ja av relasjonell kunnskap overhodet. Anerkjennelsen av det uerstattelige og umistelige kan markere begynnelsen på et paradigmeskifte.

Vi søker tekster som belyser skjønnheten, verdigheten, den vitale betydningen og den symbolske kraften til et bestemt landskap, en naturart, et økosystem. Vi oppfordrer til utforskning av det kritiske potensialet som ligger i ideen om det «umistelige» – som et motpunkt til den dominerende ideologien om erstatningsevne, bytteverdi og markedsdrevet logikk. Enhver sammensmeltning av estetisk erfaring, etisk motstandsarbeid og levende forbindelser til en natur som motstår forsømmelse og ødeleggelse, er verdt å skrive om og kultivere, også for å ære Thomas Hylland Eriksens livsverk som fikk sin kraftfulle avslutning med boken Det umistelige.

Red.

Tidligere artikler i serien:

Biskop Sunniva Gylver: Om Gud, natur, kontemplasjon og aksjon

David Zimmerman: Klyvnad och kärlek

Anders Dunker: Frem til naturen!