Religious, philosophical, and cultural traditions have been getting a bad press since the dawn of modernity. Bacon’s recommendation to smash the idols of the past and Descartes’s doubt prompting him to do away with every established certainty except for that of the cogito have cast all “received knowledge” in a negative light. For the philosophers of early modernity, tradition was the realm of stagnation, a suffocating and mystifying veil that had to be torn and destroyed for human emancipation to stand a chance. Against traditions of every stripe, they sought to start afresh from a blank page unburdened by the past, from what is given and received solely by and from oneself.

It doesn’t take a very deep analysis to realize that theirs is a cartoon-like view of tradition. Because oral wisdom and knowledge written in the form of texts are passed on from one generation to another, the body of tradition moves; it is not at all static. This body should be seen within the panorama of time, rather than space, in which no single text or oral narrative stays the same. The joints of a tradition’s body are the moments and lines of transmission, translation, and reinterpretation. Shuttled across these lines, something is lost, other bits are preserved, and still others are maintained in a transformed state. The combination of continuity and discontinuity is the basic structure of a joint, which tradition itself aspires to represent in its inter-temporal movement, delivering the past to the future or deriving the future from the past.

By doing away with tradition, modernity dares to carve history at its joints (to borrow an expression from Plato and Zhuang Zhou), to cut the transmission lines extending, with the inevitable breaks and interruptions, from the past to the present. But a living tradition, too, can suffer from arthritis, when, for example, the weight of accruing exegetical materials is so immense that it immobilizes its body, prevents reception in the midst of receptive zeal, and exerts ever increasing pres- sure on its joints.

When, in works such as Analyses Concerning Active and Passive Syntheses, Edmund Husserl deals with the sedimentation (Sedimentierung) of experience, he resorts to a geological term to describe the deadening force of growth, development, and temporal unfolding, in a word, of life itself in its objective products: “Every accomplishment of the living present, that is, every accomplishment of sense or of the object becomes sedimented in the realm of the dead, or rather, the dormant horizonal sphere, precisely in the manner of a fixed order of sedimentation: while at the head, the living process receives new, original life, at the feet, everything that is, as it were, in the final acquisition of the retentional synthesis, becomes steadily sedimented.” This process becomes acute within the cumulative experience of a tradition, where “the realm of the dead” is not a metaphorical term for experience, which has ebbed away from our living perceptual present, but the actual realm of dead authors and artists, of works that have outlived the worlds wherein they were created, of images, ideas, texts, and artifacts that turn either into fetishes or into a more or less undifferentiated mass of cultural heritage.

Perhaps, an arthrological term is preferable to the geological one, which Husserl favored to describe this process. The “fixed order of sedimentation” is external and inorganic, whereas arthritic afflictions are those of an articulated living body. Among these, gout stands out, a type of arthritis that is “a deposition disease, and is therefore defined as the presence of monosodium urate crystals (MSUCs) in tissues, most commonly in articular and periarticular structures such as cartilage, tendons, and synovial membranes of joints and bursae.” Painful crystallization at the joints, the accumulation of mineral, inorganic elements in parts of an organism where they do not belong, is more fit- ting as a diagnosis of arthritic traditions. With a single proviso: pain is a reminder that something is amiss in the hardening of structures which should be flexible, while sedimentation covers the living impulse over in such a way that the covering over is itself covered over, inaccessible to consciousness.

Looming large, standing in the way of the task as it appears within the confines of the present study, is nihilism— the arthritis of spirit, including of spirit conjugated and coeval with matter.

The arthritis of tradition exceeds the scope of texts and their interpretations. The locus of concern in our arthritic societies is meaning itself – not the meaning that was crystal- clear and glaring at some point in history only to be lost (this conservative lament is as inane as the uncompromising opposition to tradition), but meanings yet to be found, those that, signaled in the past, beckon from the future, finite yet inexhaustible. They are the meanings that are virtually indistinguishable from the senses of existence and that announce themselves as lacunae, either viscerally painful or inspiring an ongoing search. In the worst-case scenario, the question of meaning is met with a shrug of indifference under a strong cultural anesthesia, which converts the gout of traditions and the cut of modernity into the geological forces of sedimentation.

···

In an arthritic society, where ideational, political, textual, and other joints undergo debilitation, stiffening, inflammation, and chronic degradation, there is no task more urgent than to care for and to cure articulations. Carving reality at its joints will spell out an unmitigated disaster, unless one responds to this act by mending the world at its joints. Looming large, standing in the way of the task as it appears within the confines of the present study, is nihilism— the arthritis of spirit, including of spirit conjugated and coeval with matter. Behind the scenes of its pompous definitions, nihilism is the massive breakdown of articulations, leading to objective non-differentiation and subjective indifference. Arthrosophy is a medicine against nihilism. Apply it daily and nightly, in generous doses, and keep the joints of meaning working.

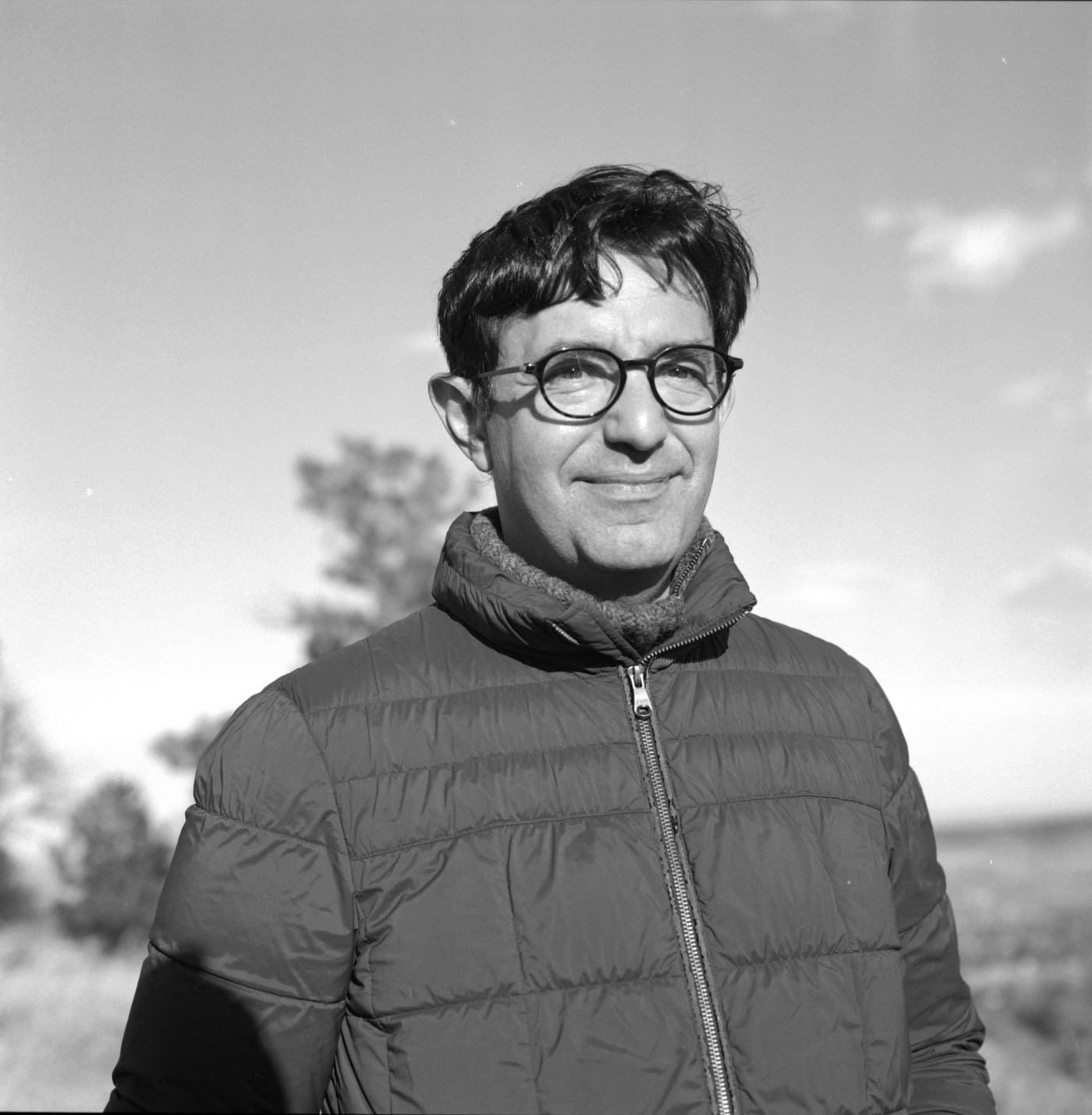

Michael Marder is IKERBASQUE Research Professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of the Basque Country (UPV-EHU), Vitoria-Gasteiz. His most recent books include The Phoenix Complex (2023), Time Is a Plant (2023), with Edward S. Casey, Plants in Place (2024), Eco-Freud (2025), Metamorphoses Reimagined (2025), with Anais Tondeur, Fiori di fuoco (2025), and Of Joints and Other Articulations (2026). More information at michaelmarder.org.

NWCC give thanks to Michael Marder for this kind permission to present an excerpt from his new book, out these days, Of Joints and Other Articulations. The Futures of Arthrosophy.

Leave a Reply